Artane

"Effective artane 2mg, pain medication for old dogs".

By: G. Vatras, M.S., Ph.D.

Clinical Director, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry

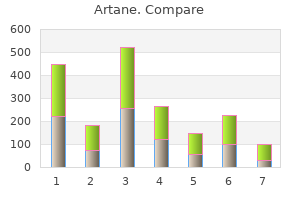

Jian Qin best treatment for shingles nerve pain artane 2mg with amex, Kevin Crowston west virginia pain treatment center morgantown wv artane 2 mg low cost, Charlotte Flynn, and Arden Kirkland, Development and Dissemination of a Capability Maturity Model for Research Data Management Training and Performance Assessment: A Final Report to the Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research, School of Information Studies, Syracuse University, accessed November 15, 2015, datacommunity. Australian National Data Services, "Research Data Management Framework: Capability Maturity Guide," accessed November 13, 2015. Cheryl Thompson, Charles Humphrey, and Michael Witt, "Exploring Organizational Approaches to Research Data in Academic Libraries: Which Archetype Fits Your Library? Compute Canada, "Compute Canada and the Canadian Association of Research Libraries Join Forces to Build a National Research Data Platform," accessed February 3, 2016. Baker, and Timothy DiLauro, "Levels of Services and Curation for High Functioning Data" (presentation at the 8th International Digital Curation Conference, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, January 1417, 2013). Traugott, "Sharing Research Data in the Social Sciences," In Sharing Research Data, edited by Stephen E. Development and Dissemination of a Capability Maturity Model for Research Data Management Training and Performance Assessment: A Final Report to the Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research. Broadly speaking, while library service models continue to evolve to meet the data management needs of researchers accountable to emerging funder requirements, it remains true that many librarians seek clarification about their role in support of data curation. Additionally, the model is understood to be nonlinear in the sense that data do not necessarily move in sequence from one repository setting to another, but may be hosted or mirrored across systems. As the context changes, so does the community served by the corresponding repository, which necessarily impacts the services provided to manage data in that context. As an example, a short- or near-term repository may commit to providing services or taking necessary actions to transform, migrate, or curate data for five Extending Data Curation Service models 173 years. In the event long-term support is required, the migration to another repository altogether, perhaps one with a five-to-ten-year remit, becomes a relay or a handoff. This model includes dark archiving, or periods during which no archive is able to provide public access to the data, with the expectation that appropriate preservation practices are in place to successfully recover the data when necessary. This is a significant issue, as a lack of distinction between these concepts can result in noncompliance and put data at risk. An illustrative example is provided by Choudhury, who relates how project team members from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey assumed that their data were sufficiently archived because they had been securely stored and backed up. As noted in the literature, coverage for data curation across the life cycle is well established within disciplines such as astronomy and certain subfields of biology. This is a two-fold problem in that a given discipline may on the one hand lack established repositories, while on the other hand available repositories may not provide sufficient preservation support to satisfy funder expectations. For example, Castelli and colleagues enumerate multiple barriers that impact data discovery and preservation among data centers and research digital libraries. Alignment is here considered from multiple perspectives, including administrative-level collaborations, the participation of functional and subject area librarians, and system capabilities. Extending Data Curation Service models 175 At the grassroots level, discussions of librarian roles in support of data curation may distinguish between subject area and functional expertise. For example, Cragin and colleagues and McLure and colleagues described the differing perceptions of researchers regarding concerns and expectations for sharing data and the corresponding service implications for repository builders. However, for the purpose of defining an extensible process model, the scenarios and strategies below are organized into three broadly defined phases: defining stakeholder interactions and requirements, harvesting and metadata processing, and content curation and packaging. Minimally, this involves securing permission to harvest and republish the data, either formally via a submission agreement or informally through e-mail or verbal agreement. Additionally, details about which data to transfer along with a proposed schedule should be documented with the necessary authorizations. If the data to be mirrored are not subject to restrictions that would prevent mirroring, such formal agreements may not be necessary. Ultimately, boilerplate language was included as rights metadata within item records with a reference to the full policy online. Once stakeholder roles and any conditions for access and use have been addressed, the harvest and ingest process can be further broken down into defining and fulfilling requirements around metadata and content modeling. In some cases, documentation of best practices and recommended cross-walks will be available.

It is likely the frustrations of confusion pain medication for dogs with hip problems cheap artane express, memory loss marianjoy integrative pain treatment center cheap 2mg artane with visa, and these other symptoms cause some of these mood changes. Changes in the brain may also affect their ability to control their emotions- they may not have a "filter. This is due to the overall changes caused by the disease, but people may also experience personality changes. Confusion, disorientation, and memory loss may cause a person to not know what they should be doing. She or he may also forget how to do things, so she or he may just not do anything at all. But it is important to understand that every person will not experience the same symptoms or progress at the same rate. Validation Therapy is a method of communicating with older adults with dementia that focuses on the caregiver using an empathic attitude and a holistic approach to the resident. There is no clear line between what is "normal" and a disease, so people are encouraged to get themselves evaluated if they are concerned about their memory. If symptoms are present that are interfering with daily functioning, then that may be a sign of pathology and an individual should be evaluated by a physican. On the other hand, we cannot assume that an older person who has memory problems is "just getting old". Cognitive impairment and dementia may be used interchangeably, but they are not necessarily the same. There are some instances in which a person has cognitive impairment but not dementia. While dementia is a common type of cognitive impairment, there are other causes of cognitive impairment. They may be: o Developmental disabilities such as mental retardation, cerebral palsy, and autism. Although the majority of individuals in assisted living are older adults, you may also care for younger individuals with cognitive impairment due to the above causes. What is important to remember is that people with any type of cognitive impairment may need additional assistance and special types of care. Many of the strategies provided in this chapter can be used with people with different types of cognitive impairment. Aphasia is the medical term that refers to the inability to communicate effectively. Agnosia is another medical term that refers to the inability to recognize objects or people or to interpret sensory signals like pain, hunger, and thirst. As we go through some communication challenges, you will see how aphasia and agnosia are the reason behind some of these challenges. Being patient and supportive gives the person the opportunity to try to express herself or himself. It is important to let them know you are listening to them 439 and will give them a chance to try to say what is on their mind. Criticizing or correcting someone will only result in them getting frustrated, angry, or agitated. Rather than try to correct what they are saying, try to look beyond the words to see what they could mean. For example, if a person says, "Today is my birthday", it is not important to correct them and tell them it is not. Is she or he reminiscing about good times she or he had at 440 birthday celebrations in the past? If you are trying to help someone with something and she will not let you, give her a few moments to cool down and come back in a few minutes. If you argue with the person it will only escalate the situation and the person will become more upset. Offer a guess Sometimes you can offer a guess to someone who is trying to communicate. If the person knows and trusts you, she will be more likely to accept your guess without getting upset. Encourage unspoken communication Ask the person to use gestures to say what they are trying to say. Discussion o Answer: When a person says "I want to go home" she might not be thinking of a physical place or her actual home.

Order artane with a visa. Alternatives to Opioid Pain Medications.

This competitive advantage serves to counteract the effects of the above-mentioned market failure joint & pain treatment center order genuine artane on line. In order to obtain a patent treating pain in dogs with aspirin order artane from india, the innovation must be inventive or not obvious; and it must be novel, in the sense of not being previously known through public use or publication (Lesser, 2002). A patent can be obtained to cover, a product per se (in itself), a process, or a product derived through a process; it may be dependent on previous patents. The requirement for a description of the invention to accompany the application, in such a way that a person "skilled in the art" is able to reproduce it, promotes the dissemination of information and may stimulate research in related fields (ibid. While patents may serve to promote innovations, it must be recognized that once a new product has been developed, the existence of a patent inhibits competition and thereby reduces the availability of the product. The balance between the two effects, and hence the outcome in terms of the economic benefits to society as a whole, is a matter of complex interactions between the length and scope of the patent and the nature of demand for the product (Langinier and Moschini, 2002). Moreover, the propensity of patents to promote innovation has sometimes been challenged. Criticisms are advanced on the Box 44 the first patented animal While patenting has a long history, the inclusion of living things under patent laws is a relatively recent phenomenon. This text box focuses on historical developments in the United States of America related to the applicability of patents to living things and leading to the first case of a patent on a higher animal. Patent law in the United States of America dates back to 1793, but the original statute makes no reference to living things. Indeed, a ruling of 1889 established a precedent indicating that "products of nature" could not be patented. The first provision specifically related to the patenting of living organisms was the Plant Patent Act of 1930, which introduced a specially designed form of protection for asexually reproducing plants (except edible roots and tubers). The 1970s and 1980s saw the emergence of technologies that enabled scientists to manipulate the genomes of living organisms. Individuals or organizations undertaking these activities were in a position to claim that the resulting organisms were the products of their own inventiveness rather than simply products of nature. It was not long before the issue was tested in the courts, and in 1980 the case of Diamond vs. Chakrabarty established the precedent that micro-organisms were patentable in the United States of America. Some years later, in 1987, the question of the patentability of higher organisms also came to court. This time, the organism in question was an oyster manipulated to make it more edible. While the application was rejected, the ruling in the case of Ex Parte Allen established that there was no legal restriction to the patenting of oysters on the grounds that they are higher animals. In this case, the animal was a type of mouse developed at Harvard University for use in the study of disease. The mouse had been genetically engineered to make it highly susceptible to cancer. Not surprisingly, the production of animals deliberately rendered susceptible to a distressing disease provoked widespread public unease, and has served to fuel the controversy surrounding animal patenting. Patents and living organisms the extension of patent law to cover plants and animals, or processes related to the production or genetic manipulation of living organisms, gives rise to additional concerns. In this respect, misgivings about patenting are to some extent tied to its association with technologies such as genetic modification. Such concerns are reinforced by fears about the health or environmental impacts of these technologies (Evans, 2002). Other objections to patents on living organisms relate to the belief that natural processes are part of the common heritage of humankind, which should not be alienated for private profit. Similarly, concerns relate to the expropriation of the genetic material developed by local communities, or the associated knowledge of crop/animal breeding activities, through the granting of patents to outside interests (ibid. Moreover, in the context of food and agriculture, the impacts on food security and social justice of restricting access to animal or plant genetic resources are further causes for concern. However, prominent exceptions include the United States of America and Japan (Blattman et al. It was in the fields of medical research and pharmaceuticals that the first legal battles related to granting patents on higher animals were fought out (Box 44). The emergence of animal patenting in the field of food and agriculture has lagged someway behind. However, among the species covered by this Report, no examples of patents granted on any breeds or types of animal intended for food production could be found at the time of writing.

Frederic Wood Jones treatment for uti back pain discount artane 2 mg free shipping, one of the leading anatomist-anthropologists of the early 1900s advanced diagnostic pain treatment center yale buy 2 mg artane visa, is usually credited with the Arboreal Hypothesis of primate origins (Jones 1916). This hypothesis holds that many of the features of primates evolved to improve locomotion in the trees. For example, the grasping hands and feet of primates are well suited to gripping tree branches of various sizes and our flexible joints are good for reorienting the extremities in many different ways. A mentor of Jones, Grafton Elliot Smith, had suggested that the reduced olfactory system, acute vision, and forwardfacing eyes of primates are an adaptation to making accurate leaps and bounds through a complex, three-dimensional canopy (Smith 1912). The forward orientation of the eyes in primates causes the visual fields to overlap, enhancing depth perception, especially at close range. Evidence to support this hypothesis includes the facts that many extant primates are arboreal, and the primitive members of most primate groups are dedicated arborealists. The Arboreal Hypothesis was well accepted by most anthropologists at the time and for decades afterward. Visual Predation Hypothesis In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Matt Cartmill studied and tested the idea that the characteristic features of primates evolved in the context of arboreal locomotion. Cartmill noted that squirrels climb trees (and even vertical walls) very effectively, even though they lack some of the key adaptations of primates. As members of the Order Rodentia, squirrels also lack the hand and foot anatomy of primates. They have claws instead of flattened nails and their eyes face more laterally than those of primates. Cartmill reasoned that there must be some other explanation for the unique traits of primates. He noted that some non-arboreal animals share at least some of these traits with primates; for example, cats and predatory birds have forward-facing eyes that enable visual field overlap. Cartmill suggested that the unique suite of features in primates is an adaptation to detecting insect prey and guiding the hands (or feet) to catch insects (Cartmill 1972). His hypothesis emphasizes the primary role of vision in prey detection and capture; it is explicitly comparative, relying on form function relationships in other mammals and nonmammalian vertebrates. According to Cartmill, many of the key features of primates evolved for preying on insects in this special manner (Cartmill 1974). Primate Evolution 277 Angiosperm-Primate Coevolution Hypothesis the visual predation hypothesis was unpopular with some anthropologists. Another is that, whereas primates do seem well adapted to moving around in the smallest, terminal branches of trees, insects are not necessarily easier to find there. A counterargument to the visual predation hypothesis is the angiosperm-primate coevolution hypothesis. Primate ecologist Robert Sussman (Sussman 1991) argued that the few primates that eat mostly insects often catch their prey on the ground rather than in the fine branches of trees. Furthermore, predatory primates often use their ears more than their eyes to detect prey. Finally, most early primate fossils show signs of having been omnivorous rather than insectivorous. Fruit (and flowers) of angiosperms (flowering plants) often develop in the terminal branches. Therefore, any mammal trying to access those fruits must possess anatomical traits that allow them to maintain their hold on thin branches and avoid falling while reaching for the fruits. Primates likely evolved their distinctive visual traits and extremities in the Paleocene (approximately 65 million to 54 million years ago) and Eocene (approximately 54 million to 34 million years ago) epochs, just when angiosperms were going through a revolution of their own-the evolution of large, fleshy fruit that would have been attractive to a small arboreal mammal. Sussman argued that, just as primates were evolving anatomical traits that made them more efficient fruit foragers, angiosperms were also evolving fruit that would be more attractive to primates to promote better seed dispersal. This mutually beneficial relationship between the angiosperms and the primates was termed "coevolution" or more specifically "diffuse coevolution. Tab Rasmussen noted several parallel traits in primates and the South American woolly opossum, Caluromys. He argued that early primates were probably foraging on both fruits and insects (Rasmussen 1990).