Viagra Jelly

"Buy 100 mg viagra jelly with visa, varicocele causes erectile dysfunction".

By: X. Jensgar, M.S., Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Indiana University School of Medicine

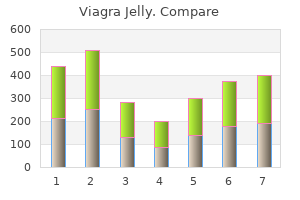

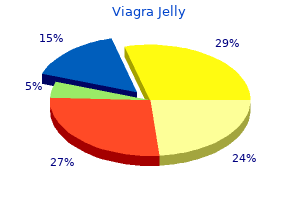

The proportions of low-weight births were lowest in Nordic countries (Iceland erectile dysfunction pills that work generic viagra jelly 100mg, Finland fast facts erectile dysfunction buy 100mg viagra jelly, Sweden, Norway, with the exception of Denmark) and Estonia, with less than 5% of live births defined as low birth weight. Despite the widespread use of a 2 500 grams limit for low birth weight, physiological variations in size occur across different countries and population groups, and these need to be taken into account when interpreting differences (Euro-Peristat, 2013). Some populations may have lower than average birth weights than others because of genetic differences. There are several reasons for this rise, including a growing number of multiple pregnancies mainly as a result of the rise in fertility treatment, and a rise in maternal age (Delnord et al. Another factor which may explain the rise in low birth weight infants is the increased use of delivery management techniques such as induction of labour and caesarean delivery, which have increased the survival rates of low birth weight babies. In Japan, this increase can be explained by changes in obstetric interventions, in particular the greater use of caesarean sections, along with changes in maternal socio-demographic and behavioural factors (Yorifuji et al. In Greece, the rise in the proportion of low birth weight babies started in the mid-1990s, well before the economic crisis, and peaked in 2010. Some researchers have suggested that the high rates of low birth weight babies between 2009 and 2012 were linked to the economic crisis and its impact on unemployment rates and lowering family incomes in Greece (Kentikelenis, 2014). Comparisons of different population groups within countries indicate that the proportion of low birth weight infants may also be influenced by differences in education level, income and associated living conditions. Similar differences have also been observed among the indigenous and nonindigenous populations in Australia, Mexico and New Zealand, often reflecting the disadvantaged living conditions of many of these mothers. The proportion of low birth weight infants is also generally higher among women who smoke than for non-smokers. This threshold is based on epidemiological observations regarding the increased risk of death to the infant and serves for international comparative health statistics. The number of low weight births is expressed as a percentage of total live births. Euro-Peristat (2013), European Perinatal Health Report: the Health and Care of Pregnant Women and their Babies in 2010, Luxembourg. Low birth weight infants, 2013 (or nearest year) % of newborns weighing less than 2 500 g 9. A commonly asked question relates to selfperceived health status, of the type: "How is your health in general For the purpose of international comparisons, cross-country variations in perceived health status are difficult to interpret because responses may be affected by the formulation of survey questions and responses, and by social and cultural factors. In addition, since older people report poor health more often than younger people, countries with a larger proportion of aged persons will also have a lower proportion of people reporting to be in good health. New Zealand, Canada, the United States and Australia are the four leading countries, with more than 85% of people reporting to be in good health. On the other hand, less than half of adults in Japan, Korea and Portugal rate their health as being good. The proportion is also relatively low in Estonia, Hungary, Poland, Chile and the Czech Republic, where less than 60% of adults consider themselves to be in good health. There are large disparities in self-reported health across different socio-economic groups, as measured by income or education level. These disparities may be explained by differences in living and working conditions, as well as differences in lifestyles. In addition, people in low-income households may have limited access to certain health services for financial or other reasons (see Chapter 7 on "Access to care"). A reverse causal link is also possible, with poor health status leading to lower employment and lower income. Greater emphasis on public health and disease prevention among disadvantaged groups, and improving access to health services may contribute to further improvements in population health status in general and reducing health inequalities. Survey respondents are typically asked a question such as: "How is your health in general Second, there are variations in the question and answer categories used to measure perceived health across surveys and countries.

The United States impotence of organic origin discount viagra jelly 100mg otc, Canada impotence lisinopril best order viagra jelly, Australia and Mexico have achieved remarkable progress over the past few decades in reducing tobacco smoking among adults and have very low rates now, but they face the challenge of tackling relatively high rates of overweight and obesity among children and adults. Some countries like Italy and Portugal currently have a relatively low rate of obesity among adults, but the current high rate of overweight and obesity among children is likely to translate into higher rates among adults in the future. Other countries like Turkey and Greece have relatively low levels of alcohol consumption, but still have a way to go to reduce tobacco smoking. Alcohol consumption remains high in Austria, Estonia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, France and Germany, although the overall level of consumption has come down in many of these countries over the past few decades (see the indicator on alcohol consumption in Chapter 4). In the United States, the percentage of the population uninsured has started to decrease significantly in 2014, following the implementation of the Affordable Care Act which is designed to expand health insurance coverage. In Greece, the response to the economic crisis has reduced health insurance coverage among people who have become long-term unemployed, and many self-employed workers have also not renewed their health insurance plans because of reduced disposable income. However, since June 2014, uninsured people are covered for prescribed pharmaceuticals and for services in emergency departments in public hospitals, as well as for non-emergency hospital care under certain conditions. The financial protection that people have against the cost of illness depends not only on whether they have a health insurance, but also on the range of goods and services covered and the extent to which these goods and services are covered. In countries like France and the United Kingdom, the amount that households have to pay directly for health services and goods as a share of their total consumption is relatively low, because most such goods and services are provided free or are fully covered by public and private insurance, with only small additional payments required. Some other countries, such as Korea and Mexico, have achieved universal (or quasi-universal) health coverage, but a relatively small share of the cost of different health services and goods are covered, leaving a significant amount to be paid by households. Direct out-of-pocket payments can create financial barriers to health care, dental care, prescribed pharmaceutical drugs or other health goods or services, particularly for low-income households. The share of household consumption spent on direct medical expenditure is highest in Korea, Switzerland, Portugal, Greece and Mexico, although some of these countries have put in place proper safeguards to protect access to care for people with lower income. The share of the population reporting such unmet medical care needs was highest in Greece and Poland, and lowest in the Netherlands and Austria. In nearly all countries, a higher proportion of the population reports some unmet needs for dental care, reflecting that public coverage for dental care is generally lower. Waiting times for different health services indicate the extent to which people have timely access to care for specific interventions such as elective surgery. Denmark, Canada and Israel have relatively low waiting times for interventions such as cataract surgery and knee replacement among the limited group of countries that provide these data, while Poland, Estonia and Norway have relatively long waiting times. Based on the available data, no country consistently performs in the top group on all indicators of quality of care (Table 1. This suggests that there is room for improvement in all countries in the governance of health care quality and prevention, early diagnosis and treatment of different health problems. The United States is doing well in providing acute care for people having a heart attack or a stroke and preventing them from dying, but is not performing very well in preventing avoidable hospital admissions for people with chronic conditions such as asthma and diabetes. The reverse is true in Portugal, Spain and Switzerland, which have relatively low rates of hospital admissions for certain chronic conditions, but relatively high rates of mortality for patients admitted to hospital for a heart attack or stroke. Finland and Sweden do relatively well in having high survival of people following diagnosis for cervical, breast or colorectal cancer, while the survival for these types of cancer remains lower in Chile, Poland, the Czech Republic, the United Kingdom and Ireland. An important pillar to achieve progress in the fight against cancer is to establish a national cancer control plan to focus political and public attention on performance in cancer prevention, early diagnosis and treatment. Health care resources Higher health spending is not always closely related to a higher supply of health human resources or to a higher supply of physical and technical equipment in health systems. Following the United States, the next biggest spenders on health are Switzerland, Norway, the Netherlands and Sweden, whereas the lowest per capita spenders are Mexico and Turkey (Table 1. Health spending per capita is also relatively low in Chile, Poland and Korea, although it has grown quite rapidly over the past decade. Greece, Austria and Norway have the highest number of doctors per capita, while Switzerland, Norway and Denmark have the highest number of nurses. Some Central and Eastern European countries such as Hungary, Poland and the Slovak Republic continue to have a relatively high number of hospital beds, reflecting an excessive focus of activities in hospital. The number of hospital beds per capita is lowest in Mexico, Chile, Sweden, Turkey, Canada and the United Kingdom. Relatively low number of hospital beds may not create any capacity problem if primary care systems are sufficiently developed to reduce the need for hospitalisation.

Buy viagra jelly 100 mg line. How Common is Erectile Dysfunction - 4 things you will want to know.

They are seen almost exclusively in young-to-middle-age patients erectile dysfunction new drug generic viagra jelly 100mg online, and they are exacerbated by increased adrenergic tone erectile dysfunction drugs wiki discount viagra jelly 100mg overnight delivery. However, since these arrhythmias are often localizable, they are quite amenable to radiofrequency ablation, which is reported to be completely effective in over 80% of cases. The arrhythmia is not associated with exercise, and symptoms are usually limited to palpitations and light-headedness. Amiodarone in patients with congestive heart failure and asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia. A comparison of electrophysiologic testing with Holter monitoring to predict antiarrhythmic drug efficacy for ventricular tachyarrhythmias. These physiologic stresses include the hemodynamic stress produced by a "chronic" high-output state, various hormonal shifts, and changes in autonomic tone. Further, women with congenital heart disease, even if successfully repaired, are especially likely to develop arrhythmias if they become pregnant. Ventricular arrhythmias are relatively rare during pregnancy unless underlying heart disease is present. Indeed, women who develop ventricular arrhythmias while pregnant should be evaluated for heart disease (including pregnancy-related cardiomyopathy), as well as accelerated hypertension and thyrotoxicosis. Using antiarrhythmic drugs in pregnancy There is a risk to both mother and fetus in using antiarrhythmic drugs during pregnancy, and these drugs should be avoided altogether unless the arrhythmias are intolerable. Furthermore, it should be recognized that conducting systematic, prospective clinical studies on the use of antiarrhythmic drugs in pregnant women has simply not been feasible and that, therefore, the quality of information we have 164 Treatment of arrhythmias in pregnancy 165 on the safety and efficacy of these drugs during pregnancy is quite poor and incomplete. The little that is known about the safe use of antiarrhythmic drugs during pregnancy will be summarized below. In addition to the usual side effects seen with quinidine, however, fetal thrombocytopenia and premature labor have been reported. Procainamide has not been reported to produce any problems uniquely associated with pregnancy, but many of the side effects of this drug-especially those related to immune reactions-should preclude its use. There is little information on the use of disopyramide during pregnancy, except that it has been used to induce labor (by increasing contractions). The American Academy of Pediatrics, however, considers these drugs to be compatible with breast-feeding. However, hypoglycemia in the newborn has been reported after mothers have taken this drug. It is excreted into breast milk, but adverse effects to babies being breast-fed have not been reported. Phenytoin, because of its extensive usage in the treatment of seizures, has been used for decades in pregnant women. Babies whose mothers have taken phenytoin during pregnancy have roughly twice the risk of developing congenital abnormalities as that of babies not exposed to this drug. Pregnant women on phenytoin should take folic acid each day to help prevent neural tube defects. Transient blood-clotting defects have been reported in newborns whose mothers were taking this drug, but vitamin K given to mothers during the last month of pregnancy prevents this problem. Phenytoin is excreted into breast milk in low concentrations, but it is considered safe to breast-feed full-term babies while taking this drug. The drug crosses the placenta and has been useful for controlling fetal supraventricular tachycardias. It is excreted into breast milk but has not been reported to cause problems in nursing infants. Propafenone should be avoided during pregnancy because particularly little information exists about its safety. Propafenone also is excreted into breast milk but has not been recognized to cause problems to nursing babies. Moricizine, like propafenone, has not been studied in pregnant women and should be avoided. It is excreted into breast milk, but problems to nursing babies have not been seen. However, reports suggest that beta blockers may be associated with low birth weights, neonatal bradycardia and hypoglycemia.

A common feature in many countries is that there tends to be a concentration of physicians in capital cities erectile dysfunction doctor boston purchase viagra jelly with paypal. For example erectile dysfunction test video order generic viagra jelly on line, Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Greece, Mexico, Portugal, the Slovak Republic and the United States have a much higher density of doctors in their national capital region. There are large differences in the density of doctors between predominantly urban and rural regions in France, Australia and Canada, although the definition of urban and rural regions varies across countries. The distribution of physicians between urban and rural regions is more equal in Japan and Korea, but there are generally fewer doctors in these two countries (Figure 7. Doctors may be reluctant to practice in rural regions due to concerns about their professional life (including their income, working hours, opportunities for career development, isolation from peers) and social amenities (such as educational opportunities for their children and professional opportunities for their spouse). A range of policy levers may influence the choice of practice location of physicians, including: 1) the provision of financial incentives for doctors to work in underserved areas; 2) increasing enrolments in medical education programmes of students coming from specific social or geographic background, or decentralising the location of medical schools; 3) regulating the choice of practice location of doctors (for new medical graduates or foreign-trained doctors); and 4) re-organising health service delivery to improve the working conditions of doctors in underserved areas and find innovative ways to improve access to care for the population. In France, the Ministry of Health launched at the end of 2012 a "Health Territory Pact" to promote the recruitment and retention of doctors and other health workers in underserved regions. This Pact includes a series of measures to facilitate the establishment of young doctors in underserved areas, to improve their working conditions (notably through the creation of new multi-disciplinary medical homes allowing physicians and other health professionals to work in the same location), to promote tele-medicine, and to accelerate the transfer of competences from doctors to other health care providers (Ministry of Health, 2015). The first results from this programme are promising, although it is still too early to reach any definitive conclusions on the costeffectiveness of various measures. In Germany, the number of practice permits for new ambulatory care physicians in each region is regulated, based on a national service delivery quota. The effectiveness and cost of different policies to promote a better distribution of doctors can vary significantly, with the impact likely to depend on the characteristics of each health system, the geography of the country, physician behaviours, and the specific policy and programme design. Policies should be designed with a clear understanding of the interests of the target group in order to have any significant and lasting impact (Ono et al. The higher level (Territorial Level 2) consists of large regions corresponding generally to national administrative regions. The lower level is composed of smaller regions classified as predominantly urban, intermediate or rural regions, although there are variations across countries in the classification of these regions. Physician density, by Territorial Level 2 regions, 2013 (or nearest year) Australia Austria Belgium Canada Chile Czech Rep. Denmark Estonia Finland France Germany Greece Hungary Israel Italy Japan Korea Luxembourg Mexico Netherlands New Zealand Norway Poland Portugal Slovak Rep. Physicians density in predominantly urban and rural regions, selected countries, 2013 (or nearest year) Urban areas Density per 1 000 population 5 4. Long waiting times for elective (non-emergency) surgery, such as cataract surgery, hip and knee replacement, generates dissatisfaction for patients because the expected benefits of treatments are postponed, and the pain and disability remains. While long waiting times is considered an important policy issue in many countries, this is not the case in others. Waiting times is the result of a complex interaction between the demand and supply of health services, where doctors play a critical role on both sides. The demand for health services and elective surgery is determined by the health status of the population, progress in medical technologies (including the increase ease of many procedures like cataract which can now be performed as day surgery), patient preferences (including their weighting of the expected benefits and risks), and the extent of cost-sharing for patients. However, doctors play a crucial role in converting the demand for better health from patients in a demand for medical care. On the supply side, the availability of different categories of surgeons, anaesthesists and other staff involved in surgical procedures, as well as the supply of the required medical and hospital equipment influence surgical activity rates. The measure used here focuses on waiting times from the time that a medical specialist adds a patient to the waiting list to the time that the patient receives the treatment. Because some patients wait for very long times, the average is usually greater than the median. In 2013/14, the average waiting times for cataract surgery was just over 30 days in the Netherlands, but much longer in Chile, Estonia and Poland (Figure 7. In the United Kingdom, the average waiting times for cataract surgery was 72 days in 2013, slightly up from 66 days in 2007. In Portugal and Spain, waiting times fell between 2007 and 2010, but has increased since then.